The Exile of Privileges or Immunities

/No State shall make or enforce any law which shall abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States . . . .

U.S. Const., amdt. XIV, § 1.

A home is a civil right. The modern legal system has a funny and incomplete way of guarding that right, which we’ll get to in a later post. But there’s a deeper question at play here: what even are “civil rights,” and how are courts supposed to enforce constitutional guarantees against their “abridg[ment]”? See, e.g., U.S. Const. amdt. I (“Congress shall make no law … abridging the freedom of speech … .”); id. amdt. XIV, § 1 (“No State shall … abridge the privileges or immunities of citizens of the United States … .”). This matters if you believe, as we do, that people should be allowed to build new homes or share where they live. That’s how today’s communities (almost) all came to be.

As we outlined in our last post, Section One of the Fourteenth Amendment contains three successive clauses that stand for freedom, the rule of law, and equality. Every civil rights case boils down to one (or more) of these three principles. When the Fourteenth Amendment was ratified in 1868, it was intended to settle a decades-long argument, revolving around slavery and culminating in the Civil War, as to how state and local governments were required to treat the people they governed. The Privileges or Immunities Clause was meant to enshrine the “unalienable” rights that Americans have always held to be self-evident.

This post has been difficult to write, because as any lawyer might tell you, the Privileges or Immunities Clause was rendered a dead letter in The Slaughter-House Cases, 83 U.S. (16 Wall.) 36 (1873). For 150 years, the Privileges or Immunities Clause hasn’t been worth anyone’s time, effort, expense, or uncertainty in court. Slaughter-House effectively precludes litigants from arguing the Privileges or Immunities Clause in federal district or circuit court: one would have to take a case all the way to the Supreme Court to get Slaughter-House overturned.

And yet no American would deny that civil rights are fundamental. Federal courts have evolved a legal doctrine under the Due Process Clause to protect some rights as such, and we’ll cover that doctrine in our next post. For today, we stress that the Fourteenth Amendment (and specifically the Privileges or Immunities Clause) was ratified to protect basic freedoms, above and beyond the abolition of slavery, and to guarantee those freedoms to every American citizen.

Here’s an abridged history of the Privileges or Immunities Clause, from 1787 through Slaughter-House’s aftermath.

ANTEBELLUM: 1787–1833

The Constitution was written in 1787 by white men who enslaved Black people taken by force from their own homes in Africa. These white men thought little of Indigenous genocide, and hardly at all of women’s suffrage. Freedom was a foundational principle, but the founders were hypocrites. They coded some of their hypocrisies into Article IV.

Section Two of Article IV still stands for one good idea, but at the time it also stood for an awful idea. The first sentence, which is still in force, holds that “[t]he citizens of each State shall be entitled to all Privileges and Immunities of citizens in the several States.” This is known as the Comity Clause, and it stands for the right to move freely about the country. See Saenz v. Roe, 526 U.S. 489, 500–04 (1999). The catch was its reservation for “citizens,” which didn’t then include Black people. Equal rights were incompatible with a nation divided around slavery, and Article IV’s Fugitive Slave Clause banned free states from protecting anyone who escaped there. There was persistent litigation around this issue before the Civil War. (The Fugitive Slave Clause was repealed by the Thirteenth Amendment, and the catch in the Comity Clause was rectified by birthright citizenship in the Fourteenth Amendment.)

As for what “Privileges and Immunities” were, the white men who litigated and judged cases back then didn’t bring or decide many cases to specify. The leading interpretation was from dicta in Corfield v. Coryell, 6 F. Cas. 546, 551–52 (C.C.E.D. Pa. 1823), which described privileges and immunities as those rights “which are, in their nature, fundamental …. [w]hat these fundamental principles are, it would perhaps be more tedious than difficult to enumerate.” The idea was expansive and intuitive: basic Declaration of Independence, natural-rights-type stuff. It included, to be sure, “the right to acquire and possess property of every kind, and to pursue and obtain happiness and safety; subject nevertheless to such restraints as the government may justly prescribe for the general good of the whole.” Id. Corfield remains important because Senator Jacob Howard quoted it “verbatim and at length” when introducing the Fourteenth Amendment for passage by the Senate. Barnett & Bernick, The Original Meaning of the Fourteenth Amendment 61–62 (2021). But the underlying case was a snoozer about New Jersey’s ban on dredging for (as opposed to gathering) oysters; the court ultimately dismissed for what we would today call lack of standing. Corfield, 6 F. Cas. at 555.

Meanwhile, what we now call the Bill of Rights did not apply to state or local governments. This is a surprising fact that few people learn about the Constitution. The First Amendment, which was originally proposed as the third in a series of twelve amendments, applied only to “Congress”; its Establishment Clause was intended in part to protect states, such as New Hampshire, Massachusetts, Connecticut, Maryland, South Carolina, and Georgia, that had established religions at the time. See Amar, Some Notes on the Establishment Clause, 2 Roger Williams U. L. Rev. 1 (1996). Writing for the Court about the Fifth Amendment’s Takings Clause, John Marshall declared that it was simply “not applicable to the legislation of the states.” Barron ex rel. Tiernan v. Mayor & City Council of Baltimore, 32 U.S. (7 Pet.) 243, 251 (1833). States had (and still have) their own constitutions and declarations of rights, whereas the antebellum Federal Constitution was almost all about the federal government.

ABOLITION: 1808–1865

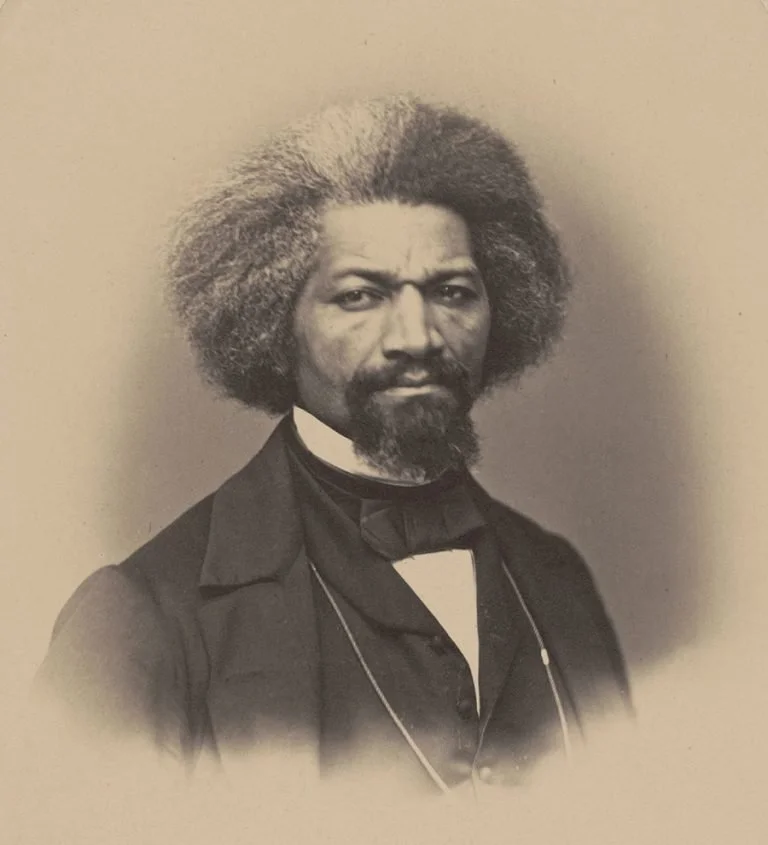

Slavery was contentious until its final and deserved demise. The Constitution, which took effect in 1789, wouldn’t let the federal government ban the importation of slaves until 1808, and the federal government did so on January 1 of that year. The political issue of the antebellum decades was slavery. Free-staters invoked Article IV’s “Privileges and Immunities” against the expansion of slavery (without success) as early as the Missouri Compromise of 1820. Barnett & Bernick, supra, at 66–69. Abolitionists debated themselves over whether to rely on the Constitution at all. The abolitionist William Lloyd Garrison held that the Constitution was illegitimate for tolerating slavery, versus the abolitionist Lysander Spooner who argued that constitutional principles, taken seriously, forbade slavery as freedom’s opposite. Id. at 90–102. Frederick Douglass, the Black voice who reached the most white ears, initially followed Garrison, but by 1851 was agreeing with Spooner. Id. (We can’t speak for Frederick Douglass, of course; you should read his work for yourself.) The movements of Black people, and of the racists who enslaved them, were often litigated until the Supreme Court decided Dred Scott v. Sandford, 60 U.S. (19 How.) 393 (1857) (consensus worst decision in Supreme Court history).

The abolitionist Republican Party came into being and displaced the Whigs. Abraham Lincoln was elected President in 1860, eleven southern states seceded, and America fought its Civil War.

AMENDMENT: 1865–1870

Martin Luther King, Jr., praised “the magnificent words of the Constitution and the Declaration of Independence” in his most famous speech, citing the “unalienable rights of life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.” King, Jr., I Have a Dream (1963); accord The Declaration of Independence (U.S. 1776). King said that

“if America is to be a great nation, this must become true.”

The Constitution was amended three times in direct response to the Civil War. The Thirteenth, Fourteenth, and Fifteenth Amendments are collectively known as the “Reconstruction Amendments,” and each of them built on the last.

The Thirteenth Amendment was ratified in 1865 to abolish slavery, and authorize Congress to legislate against slavery’s badges and incidents. This is the enforcement power that the Supreme Court much later upheld, by way of overruling The Civil Rights Cases, 109 U.S. 3 (1883), in Jones v. Alfred H. Mayer Co., 392 U.S. 409 (1968). Jones, as you’ll recall from our first post in this series, applied the Civil Rights Act of 1866 to outlaw a simple instance of private racial housing discrimination.

The Civil Rights Act of 1866 was passed after the Thirteenth Amendment but before the Fourteenth. The timing here is important. As Jones belatedly recognized in 1968, this Act was intended by Congress to make use of its new power to enforce the Thirteenth Amendment. 392 U.S. at 438–44. The Republican abolitionists who controlled Congress wanted to ensure that Black people would equally enjoy the same rights as “white citizens,” and that’s what the Act did with regard to contract and property rights. 42 U.S.C. §§ 1981, 1982. But it wasn’t clear in 1866 that the courts would uphold the Act, or that a future Congress wouldn’t repeal it. Former confederates were vying to regain power, and President Andrew Johnson (a southern Democrat) vetoed the Act, inducing Congress to override his veto. This all happened while Congress was debating what became the Fourteenth Amendment. The Congressional record is clear: the Fourteenth Amendment was designed to guarantee that the Civil Rights Act of 1866 would forever remain “the supreme Law of the Land.” U.S. Const., art. VI.

Of course the Fourteenth Amendment went on to be ratified in 1868. Section One specified that “[a]ll persons born or naturalized in the United States” were “citizens,” superseding Dred Scott and affirming that Black people, too, enjoyed fundamental “privileges or immunities” as such. U.S. Const., amdt. XIV, § 1. The Due Process Clause superseded Barron’s reading of the Fifth Amendment by expressly requiring states to provide a legal process before “depriv[ing] any person of life, liberty, or property.” Id. The Equal Protection Clause (at last) legislated the Declaration’s claim that all are created equal, and required the states to fashion their laws accordingly. And Section Five, mirroring the Thirteenth Amendment, gave Congress the power to enforce all of the Fourteenth Amendment’s provisions.

The Fourteenth Amendment completely remade the pre-Civil War federal structure of government. It is the reason that constitutional rights—freedom of speech, security in the home, due process, equal protection, etc.—are enforceable against state and local governments at all. And the Fourteenth Amendment expressly enables Congress to legislate in favor of those rights, in case state and local governments (or even private actors) fail to respect them.

The Fifteenth Amendment, ratified in 1870, closed a loophole in the Thirteenth and Fourteenth Amendments regarding the right to vote. This is a historical curiosity today, but there was an “overwhelming consensus” in the late 1860s (among white men, anyway) that “the right to vote was not a privilege of citizenship.” Barnett & Bernick, supra, at 244. The Fifteenth Amendment extended voting rights to all men regardless of race, just as the Nineteenth Amendment (1920) did for all adults regardless of gender. Because voting rights aren’t as relevant to the modern housing debate as Fourteenth Amendment rights, we’ll move on.

SLAUGHTER: 1873–1883

Trouble happens in America when white voices crowd out Black voices. White people have rights too—and it feels trite to say so—but it could well be easier for the Court to tune out when white litigants, with relatively more of the resources to get there, are the first to approach the Court with abolition-related legal questions. We can’t prove this, but it could explain the result in The Slaughter-House Cases (1873).

Slaughter-House nullified the Privileges or Immunities Clause when it was only five years old. The case is today regarded as an obsession among legal libertarians like this coauthor, whereas most lawyers simply learn as 1Ls that Slaughter-House was decided, and that was that. But Slaughter-House was important. And besides, two Justices have mused that Slaughter-House may have been wrongly decided. See, e.g., Timbs v. Indiana, 586 U.S. __ (2019) (slip op.) (Gorsuch, J., concurring; Thomas, J., concurring in the judgment).

Slaughter-House was a legal challenge by New Orleans butchers to a Louisiana law that created a corporation with a monopoly on the right to rent space for butchering. There was, to be sure, a health and safety concern at play: the Mississippi River in New Orleans was polluted at low tide by the offal and other runoff from upstream slaughterhouses, and the corporate monopoly was meant in part to ensure that all butchering would take place downstream from New Orleans. See 83 U.S. at 62. But the (presumably white) butchers didn’t argue with that. As Justice Field wrote in dissent, “the sanitary purposes of the act [could have been] accomplished” without creating a corporate monopoly, and that—requiring butchers to pay franchise fees to a specific corporation in order to do their jobs—abridged the butchers’ “right to pursue a lawful and necessary calling,” which was among the “privileges or immunities” supposed to be guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment. Id. at 87–89 (Field, J., dissenting). In the majority’s view, however, the Reconstruction Amendments were aimed at abolishing “African slavery,” and Louisiana’s slaughterhouse monopoly just wasn’t that. Id. at 68–72 (majority opinion). The monopoly scheme was upheld, and the Privileges or Immunities Clause defined downward to mean no more than what the antebellum Constitution had already guaranteed. See id. at 74–80. But as we saw above, that really wasn’t much.

Slaughter-House had immediate and lasting consequences. The day before Slaughter-House was decided, some 60–160 Black freedmen (estimates vary) were murdered by the Ku Klux Klan at a Louisiana parish courthouse in a Klan riot challenging the 1872 gubernatorial election, which a Republican reconstructionist had won. This insurrection came to be known as the Colfax massacre. Several of the Klan insurrectionists were indicted and convicted under the Civil Rights Act of 1870, which made it a federal crime to conspire against anyone’s “free exercise and enjoyment of any right or privilege granted or secured to him by the constitution or laws of the United States.” United States v. Cruikshank, 92 U.S. 542, 548 (1876). These criminal cases made their way to the Supreme Court which, after citing Slaughter-House, held that the Black freedmen’s “right and privilege to peaceably assemble” at the courthouse was not “a right granted to the people by the Constitution.” Cruikshank, 92 U.S. at 549, 551. No matter that the First Amendment explicitly protects that right: the Court ruled that the First Amendment “was not intended to limit the powers of the State governments in respect to their own citizens, but to operate on the National government alone.” Id. at 552 (citing Barron). The Court added that “[t]he [F]ourteenth [A]mendment … adds nothing to the right of one citizen [the Black freedmen] as against another [the Klan insurrectionists].” Id. at 554.

Cruikshank thus held that Congress’s power to enforce the Fourteenth Amendment, U.S. Const. amdt. XIV, § 5, did not authorize federal legislation criminalizing the “private” actions murders perpetrated by the Ku Klux Klan. 92 U.S. at 554. Cruikshank, in tandem with The Civil Rights Cases (1883), eviscerated the post-Civil War order that the Reconstruction Amendments were intended to create. As for the Civil Rights Act of 1866, the Cruikshank Court denied that the Klan’s mass murder of Black freedmen was at all “on account of their race or color.” Id. at 555. The Klan members’ convictions were thrown out. Rest in peace, anonymous freedmen, we hardly knew ye.

***

There it is: the original meaning and premature exile of the Privileges or Immunities Clause. The passage of 150 years has not wholly repaired the Fourteenth Amendment’s intended recognition of fundamental rights. Racial discrimination ran legally unchecked for a century after the Civil War, and the Bill of Rights would not be enforced against state and local governments until the 1920s. Racial redlining, which took place after that, has been formally discontinued, but never honestly dismantled by the courts.

When the Bill of Rights finally did start getting enforced, it was done (as it is today) under the aegis of the Due Process Clause. That clause, and its particular application to zoning as announced in Village of Euclid v. Ambler Realty Co., 272 U.S. 365 (1926), will be the subject of our next post.